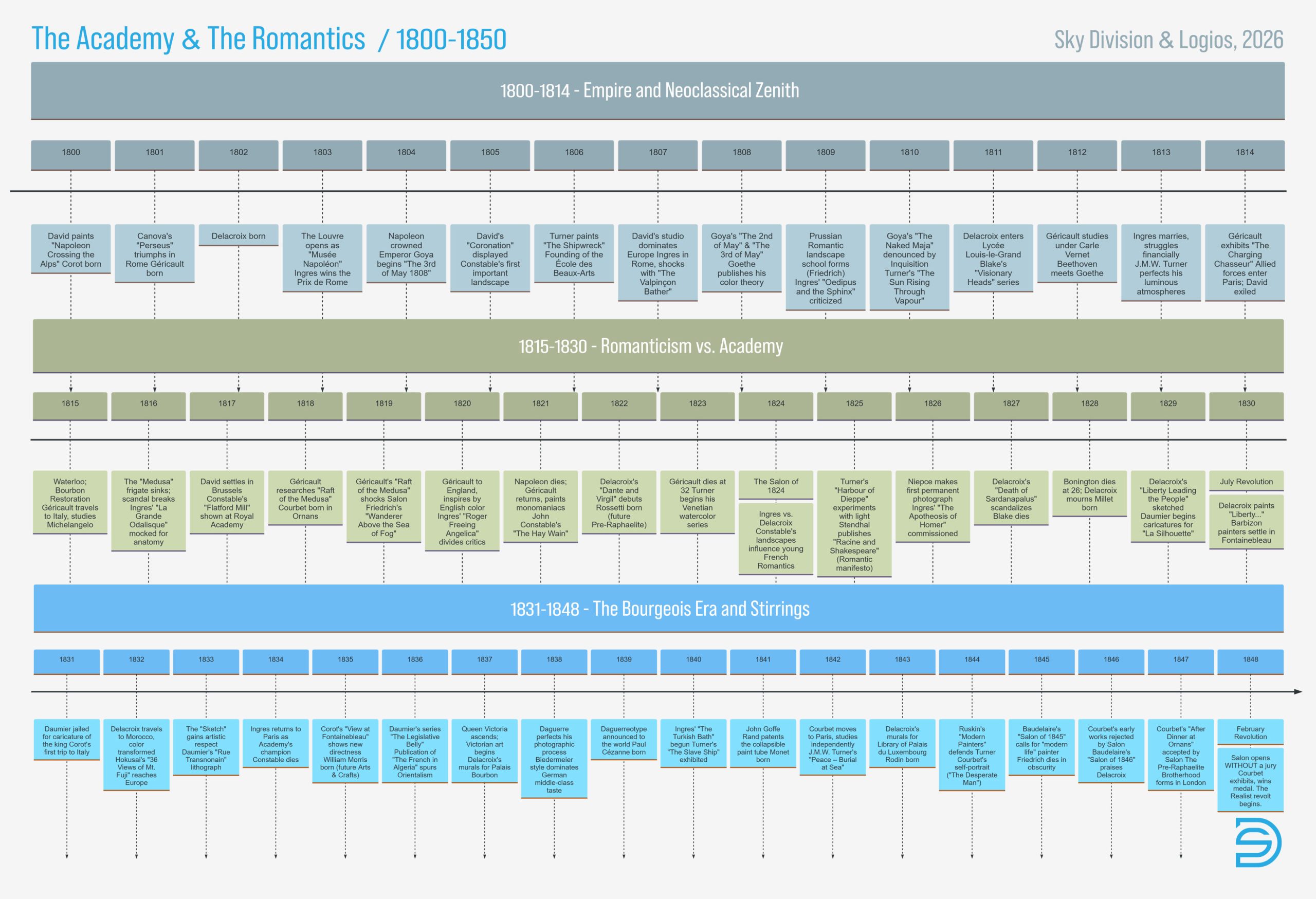

( Sky Division & Logios, 2026 – Infographics, Timelines )

During the period from 1800 to 1850, the European art world was defined by a profound tension between two dominant forces: the established Academy and the revolutionary spirit of Romanticism. This era witnessed a dynamic and often contentious dialogue between institutional authority and individual expression.

[ click expand in the lightbox, or download the graphic to view it properly ]

The Academy, epitomized by institutions like the French Académie des Beaux-Arts, represented the pinnacle of formal artistic training and official taste. It upheld a strict hierarchy of genres, with history painting – depicting classical, biblical, or historical narratives – considered the most prestigious. Academic art prized technical mastery, idealized forms, clear composition, and adherence to classical principles derived from antiquity and the Renaissance. The Academy controlled artistic careers through its salon exhibitions, which were essential for securing patronage and reputation.

In stark opposition, Romanticism emerged as a multifaceted movement that championed subjectivity, emotion, and the sublime. Reacting against the Enlightenment’s rationalism and the Academy’s rigid rules, Romantic artists sought to express intense personal feeling, imagination, and individual genius. Their subject matter shifted dramatically from classical history to contemporary literature, medieval legends, dramatic landscapes, and scenes of political upheaval. Artists like Eugène Delacroix (in contrast to the Neoclassical J.A.D. Ingres) emphasized color, dynamic movement, and exotic or emotionally charged themes to evoke passion and awe.

The conflict was not merely stylistic but philosophical. The Academy stood for order, tradition, and universal ideals, while Romanticism valued intuition, national and folk identities, and the untamed power of nature. By mid-century, this friction had fundamentally reshaped the artistic landscape, challenging the Academy’s monopoly and paving the way for subsequent movements like Realism, which would further reject idealized depictions in favor of everyday contemporary life. Thus, this half-century was a crucial battleground where the modern concept of the artist as a visionary, independent creator began to solidify against the backdrop of institutional tradition.