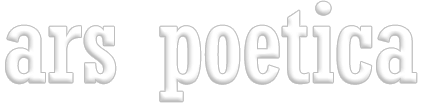

( Sky Division & Logios, 2026 – Infographics, Timelines )

The period from approximately 1700 to 1750 in European art, often termed Academic Classicism or the early phase of the Beaux-Arts tradition, represents a sophisticated consolidation of artistic principles under the growing influence of Enlightenment thought. Centered on the powerful official academies, most notably the French Académie Royale de Peinture et de Sculpture (founded 1648), this era upheld a rigorous hierarchy of genres. History painting – depicting elevated narratives from mythology, religion, and classical antiquity – remained the preeminent category, valued for its intellectual and moral edification. Portraiture, genre scenes, landscape, and still life followed in descending order of prestige.

[ click expand in the lightbox, or download the graphic to view it properly ]

Stylistically, Academic art of this period was characterized by a disciplined adherence to classical ideals: balanced composition, idealized human forms derived from Greco-Roman sculpture, and a polished, refined technique that prioritized drawing (‘disegno’) over color (‘colore’). This formalism was not merely aesthetic but philosophical, reflecting Enlightenment values of order, reason, and universal truth. Artists such as Charles-Joseph Natoire and François Lemoyne in France exemplified this style, creating grand, didactic works that celebrated civic virtue and heroic action.

Simultaneously, the early Enlightenment’s empirical spirit began to subtly influence academic practice. While the core curriculum stressed the imitation of classical masters and the human figure through life drawing, there was a growing, though cautious, engagement with scientific observation and a more structured study of anatomy and perspective. The era thus functioned as a bridge, maintaining the strict protocols and didactic mission of the 17th-century academy while gradually assimilating the rationalist inquiry that would later prompt both refinement and, eventually, challenges to its authority in the later 18th century.

***

The Academy & Early Enlightenment, 1700-1750

During the early eighteenth century, the European Enlightenment transitioned from its foundational phase into a period of institutional consolidation and public dissemination. The period from 1700 to 1750, often termed the “Academy” or “Early” Enlightenment, was characterized by the formalization of intellectual inquiry through learned societies and the gradual spread of critical ideas beyond elite circles.

Central to this era was the rise of academies and scientific societies, such as the Royal Society in London and the Académie des Sciences in Paris. These institutions provided structured forums for debate, funded research, and published journals, transforming philosophy and natural science into collaborative, progressive enterprises. They championed empirical methods and rational discourse, directly challenging traditional scholastic and religious authorities. This period also saw the flourishing of salons, particularly in France, where aristocrats and intellectuals mingled to discuss new ideas, helping to create an embryonic “public sphere”.

Intellectually, the era was dominated by the systematic philosophies of thinkers like Gottfried Wilhelm Leibniz and the popularizing efforts of figures such as Voltaire. Following the death of Louis XIV in 1715, a more liberal cultural climate emerged, especially in France, allowing for sharper critiques of church and state. Key works, including Montesquieu’s ‘Persian Letters’ (1721), used satire to question European customs and absolutist governance. The overarching project was the application of reason to all aspects of human life – society, politics, religion, and the economy – with a growing emphasis on individual liberty, tolerance, and progress.

In summary, the Academy and Early Enlightenment (1700-1750) was a pivotal phase where the radical ideas of the seventeenth century became organized, social, and increasingly public. Through academies, salons, and pioneering texts, Enlightenment principles began to permeate educated society, setting the stage for the more politically revolutionary fervor of the later eighteenth century.